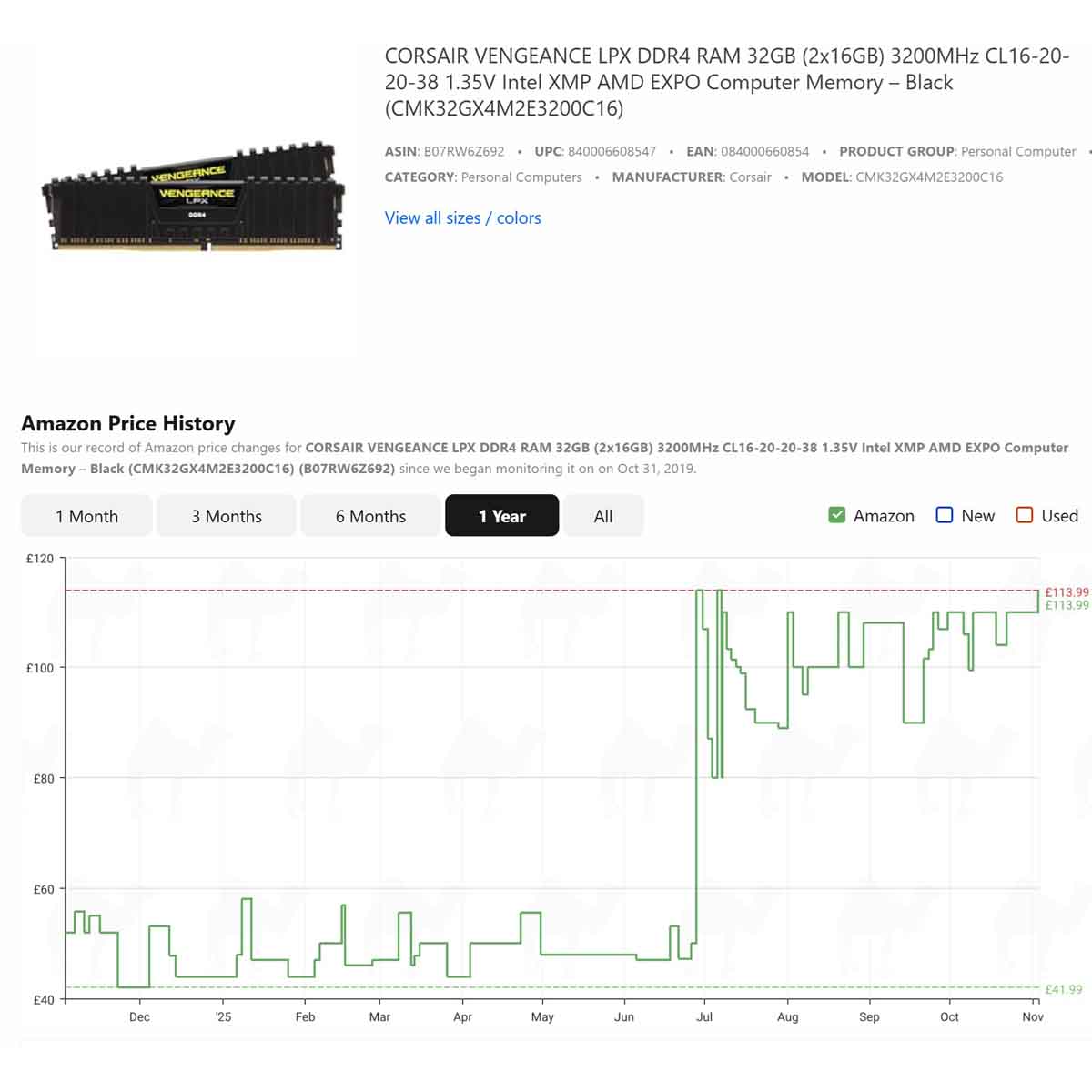

You may have had a nasty surprise if you’ve tried to spec up a new PC or upgrade your RAM recently. Upgrading your rig from 16GB to 32GB of memory would have set you back an almost throwaway cost of around £45 earlier this year, but the same dual-channel kit will have now more than doubled in price to £113.99, and it doesn’t even have any fancy RGB lighting. The cost of memory has continued to soar for the last few months, and it looks as though there’s no end in sight. What’s going on?

RAM prices have historically been highly volatile, of course. I remember several periods over the last three decades where everything from factory fires to unexpectedly high demand have sent prices going up and down like a yo-yo. In historical context, it’s something of a novelty that memory has remained comparatively cheap low for so long, while outlandish GPU inflation has instead dominated the headlines.

But now, depressingly, it’s boom time for memory again, and this time the huge demand from AI data centres is taking centre stage in the blame game. The problem is that there are only three main companies making DRAM chips at large scale – SK Hynix, Micron and Samsung – and while the tech industry expected AI to be big, no one expected it to be anywhere near this big so soon, and there are no other companies able to step in and meet the demand. AI data centres are being built at an incredibly fast pace, and they all require DRAM in various forms at massive scale.

Basically, there isn’t enough manufacturing capacity to go round. That firstly means that supply is already short, but it also means that the manufacturing of end-of-life products, such as DDR4 memory, is being turned off as manufacturers scramble to increase DDR5 production capacity.

That in turn has resulted in what market analysis firm TrendForce described as “aggressive restocking of legacy-generation products” in a report back in July, which increased inflation further. TrendForce also points out that the dwindling DDR4 memory production capacity that is available is mainly being hoovered up for use in servers, rather than PCs, leaving little stock for companies like Corsair to make gaming modules. The price of all memory is going up, but the rate of inflation is higher for DDR4 than DDR5, as you can see in the screenshot from CamelCamelCamel below.

But traditional DIMMs for PCs are just a small part of the picture here. After all, almost every computing device in the world uses DRAM in some form or another, from the memory used in smartphones and handhelds to the high-speed VRAM used in graphics cards.

Regarding the latter, as with DDR4 memory, slower and older GDDR6 memory is also being forsaken by manufacturers according to TrendForce, as faster GDDR7 memory is prioritised, with the cost of GDDR6 memory going up by up to 33 per cent. That’s potentially bad long-term news for the prices of graphics cards based on GDDR6 memory, which include new budget cards such as the RTX 5050, as well as all of AMD’s latest RDNA 4 GPUs, such as the Radeon RX 9070 XT.

This outlandish level of demand for DRAM has had a profound impact on the tech industry. DigiTimes has just reported that Samsung is apparently delaying DDR5 contract pricing to mid-November for its partners, as prices are tripling. Meanwhile, in October, chairman of PC memory maker Adata, Simon Chen, described “severe shortages” of memory in comments reported by DigiTimes. Chen says that Adata has instructed its staff to “sell sparingly and support key customers,” while describing a huge shift in market dynamics, where “our competitors in the fight for supply are no longer our peers, but giant CSPs [cloud service providers].”

When will memory become more affordable? I hate to be the bearer of doom and gloom, but I don’t expect that time to come soon. Even if the AI boom slows down, the demand for DRAM will still be way bigger than anyone anticipated a few years ago, and building extra manufacturing capacity takes a long time.

If the AI boom does turn out to be a bubble that bursts catastrophically, then the situation is likely to change, but until then, or until manufacturing capacity is significantly expanded, we sadly need to get used to the idea of paying more for our memory.