Nvidia might be on top of the world right now, but our current AI overlord has undoubtedly unleashed some stinkers into the PC gaming landscape over the years, and it’s not the only one. AMD has produced its fair share of shockers, as have others. We thought it would be a laugh to chart the worst GPUs ever. The ones that made us screw up our faces in consternation as we ran them through the test rig, wondering what on earth the manufacturer was thinking.

Some just didn’t work properly, others had bizarrely noisy coolers, bizarrely slow memory, or far-fetched prices. Technically, a couple of these aren’t GPUs, as they lack hardware transform and lighting, but they’re all 3D graphics cards that many people would prefer to forget. Anyway, here they are – the worst of the worst.

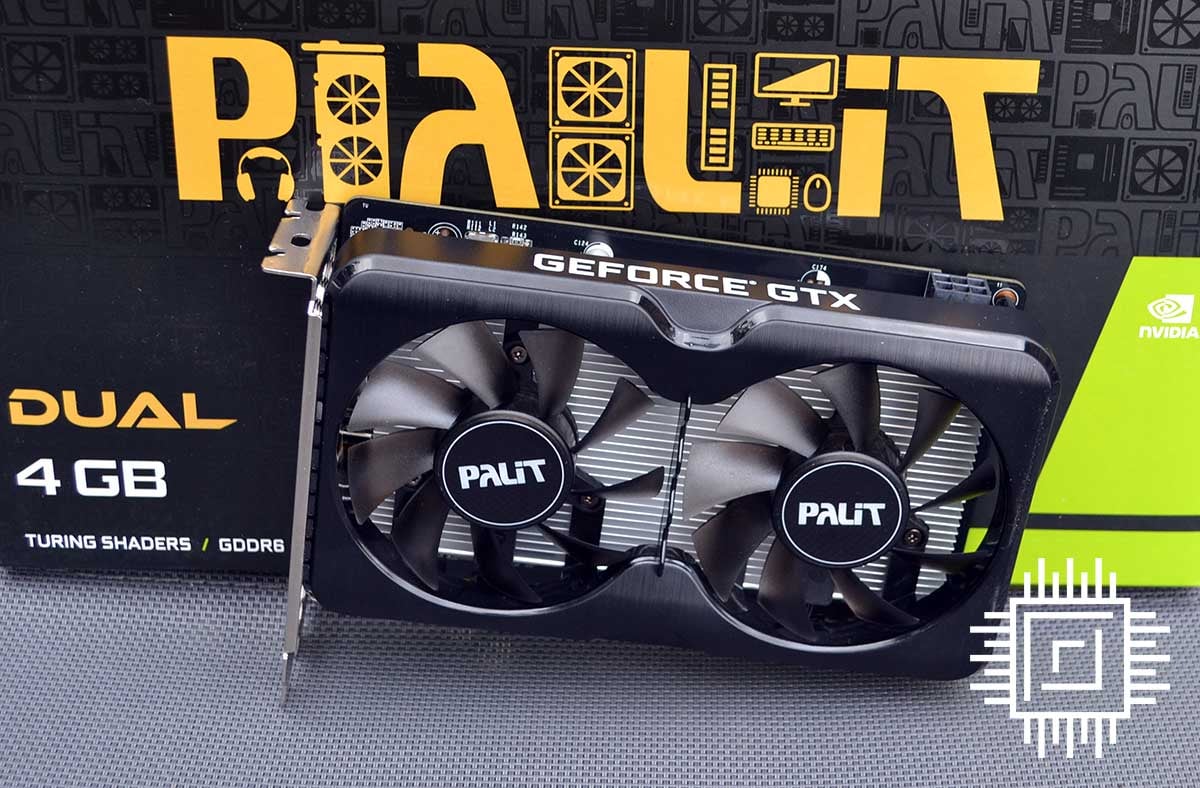

10. Nvidia GeForce GTX 1630

You only need to look at this weedy GPU to see why Nvidia decided to kill off its GTX branding. After releasing the truly awful GTX 1630, this premium three-letter initialism had been seriously devalued. Coming out in 2022, on the back of a depressing GPU shortage where we’d seen prices take off into the stratosphere, Nvidia released this budget GPU without an official price. We then watched as cards started appearing for $199 / £149 and held our heads in our hands.

There was definitely a clamour for a new sub-$200 GPU at this point, of course, but the GTX 1630 was shockingly bad for the money. It was based on the same Turing architecture as Nvidia’s other GTX 16-series cards, which had released three years earlier and was now looking very long in the tooth. There were no ray tracing or Tensor cores either, but that could be forgiven at the time if it had decent enough specs to provide solid raster performance for the price. Is that what happened? Well, no.

We watched as cards appeared for £149 and held our heads in our hands

GTX 1630 had just 512 CUDA cores, while its 4GB of GDDR6 VRAM was attached to a super-tight 64-bit memory interface, resulting in a total memory bandwidth of just 96GB/s. The specs were abysmal compared to the GTX 1660, which had launched for $219 three years earlier, with twice the memory bandwidth and well over double the number of CUDA cores.

Even the lamentable Radeon RX 6400 was significantly quicker in our GTX 1630 review, where we gave this GPU a score of just two stars. If Nvidia had called it the GT 1620, and priced it under £100, this GPU wouldn’t have been terrible. But as a GTX GPU at this price? That’s a hard nope and even two stars was generous.

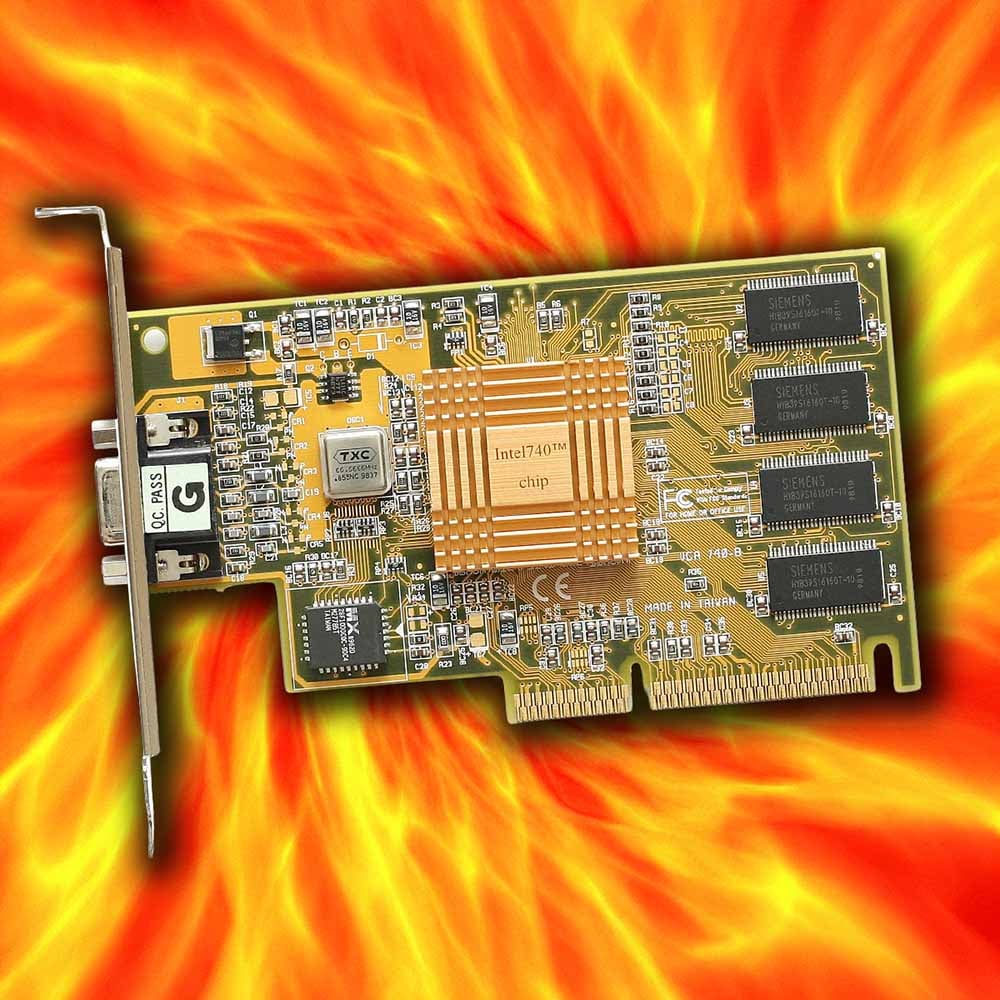

9. Intel i740

This unassuming little PCB was the bane of my life when I worked in a computer shop in the 90s, as sales were almost inevitably followed up by a frustrated tech support call a few hours later. At £30, the Intel i740 looked like an absolute bargain, especially with the Intel brand on the box. It could handle both 2D and 3D, meaning you didn’t need a separate Voodoo card to play 3D games. It also used the brand-new accelerated graphics port (AGP) interface, while separate 3D cards all still used the PCI bus. What’s not to like?

There were several problems with the i740, but the chief one was compatibility. It generally played nicely if you slotted one into a Pentium II system with a 440BX chipset, but its drivers threw their toys out the pram if you put it in a non-Intel rig, such as an AMD K6-2 system with an ALi chipset. That was a problem, as a lot of the people buying £30 graphics cards wanted to put them in cheap systems. Even if you got one working in an Intel system, performance was still disappointing, with dodgy drivers resulting in a load of game compatibility issues and weird visual artefacts.

Why fit loads of local memory to your card if you could just use system RAM?

A part of the reason for its cheap price was its lack of memory. Intel had decided to make full use of a new feature that came with the AGP bus, which was a dedicated bus for sideband addressing, which meant AGP cards could read data from system memory much quicker than PCI cards. This gave Intel a route to cost cutting. Why fit loads of local memory to your card, if you could just use system RAM via the AGP bus instead? This is why entry-level i740 cards had just 2MB of memory, on the basis that they could read from system memory to make up the shortfall.

But system RAM is no replacement for local VRAM, particularly when games started to come loaded with increasingly larger textures. What’s more, taking so much system RAM ended up taking valuable resources from the CPU, which was still a key part of the 3D graphics pipeline at this point. It also really didn’t help that Real3D (which had developed the i740 with Intel) released a PCI version with dedicated memory, and it was quicker than the AGP card. Still, at least the i740 was cheap.

8. Nvidia Titan Z

You might think RTX 5090‘s $1,999 launch price is outrageous (and you’d be right), but it looks positively generous compared to the $2,999 tag attached to Nvidia’s Titan Z. This was back in 2014 too, when a GTX 780 Ti cost less than a third of that price. In retrospect, if you’re wearing a cynical hat, it looks like Nvidia testing the water to see if people would really pay that much for a flagship card.

This dual-GPU beast also marked a complete about-face for Nvidia’s Titan brand. Until that point, Titan cards had provided a breath of fresh air, eschewing all the compatibility issues associated with dual-GPU cards in favour of a single, fully-enabled GPU. They were expensive, but if you could afford one, you would get the best Nvidia could offer without all the hassle of faffing around with SLI. Titan Z completely changed that formula for some reason, with two fully-enabled Kepler GK110B chips under its massive cooler.

It makes the RTX 5090’s price look positively generous

Make no mistake, this was a very fast card in games that scaled well with SLI – it wasn’t bad in that respect. The problem was that teaming up a pair of GTX 780 Ti cards in SLI configuration was nearly as fast, and considerably cheaper. Even AMD’s competing dual-GPU Radeon R9 295X2 cost half the price at $1,499. We looked at the three-grand price, and just couldn’t square any way to justify it. With two GPUs running at full pelt, it drew a lot of power and made a fair bit of noise as well.

With its frankly ridiculous price, while also relying on SLI to get the most out of it, Titan Z undid all that we’d loved about Titan cards until that point. Thankfully, there hasn’t been a multi-GPU Titan card since.

7. Nvidia GeForce GT 1030 DDR4

You’ll notice we’ve put ‘DDR4’ at the end of our title here, just to make it clear which card we’re discussing, which is more than Nvidia did when it released this horror of a budget GPU in 2018. Coming a year after the original GT 1030, this hobbled version replaced the GT 1030’s 2GB of high-speed GDDR5 memory with standard DDR4 RAM, and performance absolutely tanked.

This hobbled version replaced the 2GB of GDDR5 memory with standard DDR4, and performance absolutely tanked

Nobody expected the original GT 1030 to set the world alight when it came out, of course. With just 384 CUDA cores and a 64-bit memory bus, this bottom-end Pascal GPU was clearly intended for gamers who didn’t have much money to spend. You might pick one up if you just wanted a card that could play undemanding games like Fortnite, and the GDDR5 version could cope pretty well here. Indeed, GT 1030 benchmarks show Fortnite running at over 60fps at 1080p with Medium settings.

Slot the DDR4 version of the same card into your PC, though, and Fortnite performance plummets by 42% from 66fps to just 38fps, with similar drops in other games. With such a catastrophic drop in frame rates, you might expect a cheaper price, but nope, the GT 1030 DDR4 had the same $79 MSRP as its predecessor. What’s more, as both variants’ packaging sported the same GPU name, you had to look closely at the specs to see which card you were buying. With a misleading name, slow memory and rubbish performance, this card can get in the bin.

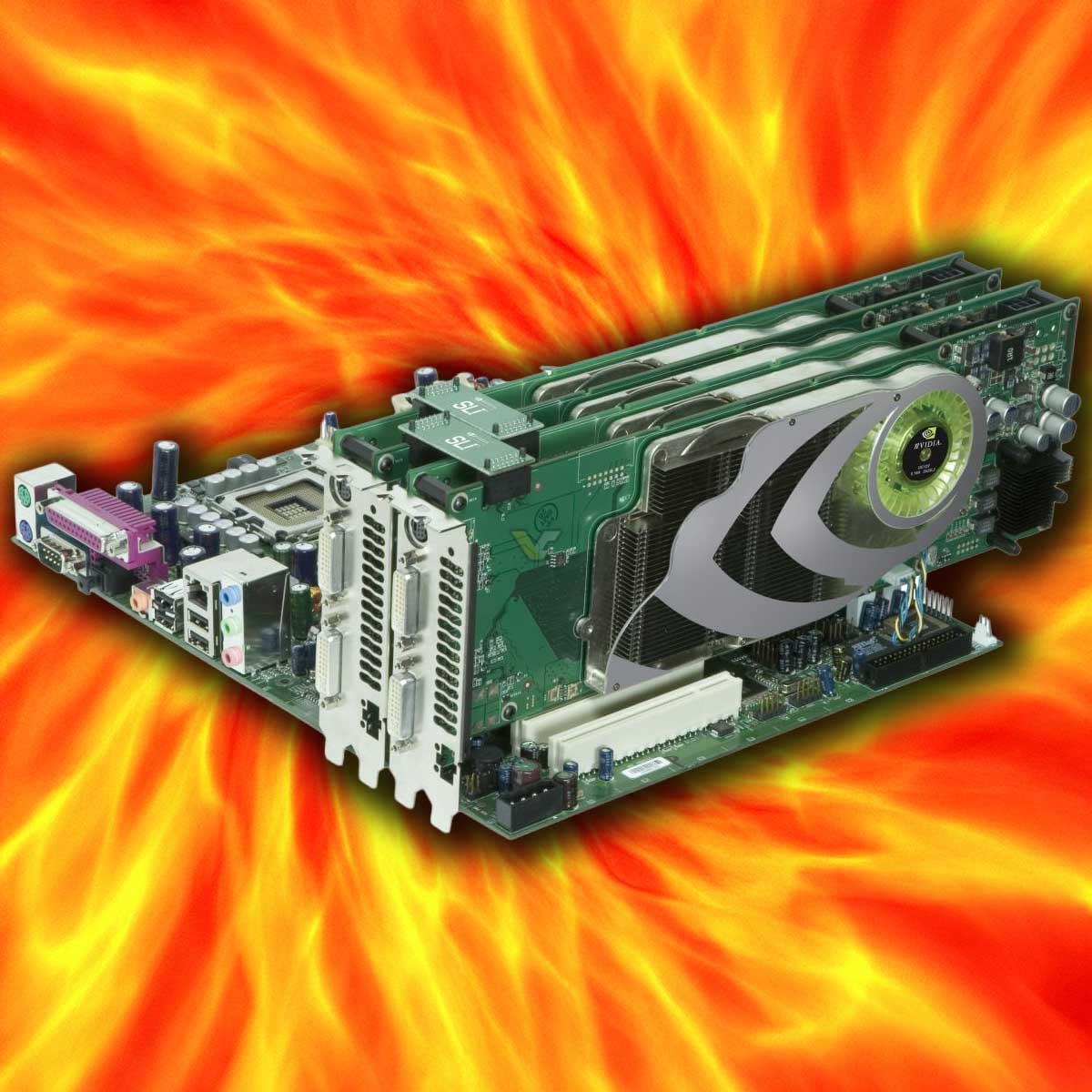

6. Nvidia GeForce 7900 GX2 Quad SLI

What’s better than two GPUs working together? Four, of course! Except, no, it really wasn’t. As SLI was now proving popular among enthusiasts with cash to splash, Nvidia came up with an idea to get four of its GPUs running together in a standard SLI motherboard. More is better, right?

Rather than using four PCIe slots, the system instead relied on installing two dual-GPU cards, corresponding with the dual 16x-sized slots on SLI motherboards. And when we say dual-GPU, what we actually mean is two cards sandwiched together to make one. Each GeForce 7900 GX2 was essentially two cards in one, so when you had two of these cards installed, it was basically four PCBs. As such, each card had a pair of G71 GPUs – the same core used in the top-end GeForce 7900 GTX. That meant you also got 1GB of GDDR3 memory split into two parts. You then bridged all the cards together with two SLI connectors.

The horrible blower coolers made a disgusting amount of noise, as they were pushed right up against PCBs

But there were problems. Lots of them. Nvidia had worked hard on its drivers and dev relations to get two cards in SLI working properly in a lot of games, even if it didn’t work in all of them. But quad SLI was a different story – flickering artefacts, corruption, freezing, and stuttering problems were common. What’s more, many games showed little performance benefit of using four cards over two, and often lacked quad-SLI profiles.

It also didn’t help that Nvidia’s Curie architecture didn’t support the latest HDR graphics tech fully – it would run, but not with anti-aliasing enabled, so you still got jagged edges. Given that ATi’s competing X1800 range could run HDR with AA, the 7900 GX2 started to look pretty silly. There was loads of GPU power, but it still couldn’t run the latest graphics tech properly.

To top it all off, the horrible blower coolers on the cards made a disgusting amount of noise, as there were four fans, three of which were right up against the next cards’ PCBs. They ate power like Hungry Hippos gobbling marbles too. Sometimes we get nostalgic for old tech, even when it didn’t work well, but we’re very glad we don’t ever have to test quad-SLI again.

5. AMD Radeon RX 6500 XT

It was a bleak time to buy a new gaming GPU at the start of 2022. Cryptominers were hoovering up every GPU in sight, eBay scalpers were inventing extraordinary prices, and the Covid pandemic had slowed down production and distribution. All this chaos did make one fact obvious, though. People were clearly willing to pay any price for a new GPU, and AMD seemingly realised it could even charge $199 for a card as bad as the AMD Radeon RX 6500 XT.

That was a lot of money for this skeleton of a GPU, which had just 4GB of VRAM

That was a lot of money for this skeleton of a GPU, which had just 4GB of VRAM attached to a tight 64-bit memory interface. Not only was that a tiny amount of VRAM, but the bus meant it had a pitiful total memory bandwidth of just 143.9GB/s. Comparatively, even its predecessor, the Radeon RX 5500 XT, launched for $169 and had 224GB/s of VRAM bandwidth.

Meanwhile, the Navi 24 GPU under its cooler only had 16 compute units, giving it a truly rubbish count of just 1,024 stream processors. Then, as an encore, AMD equipped the 6500 XT with just four PCIe Gen 4 lanes, meaning it could still only use four lanes on a PCIe Gen 3 system.

Its performance was dreadful in our Radeon RX 6500 XT review, with minimum frame rates dropping to just 8fps in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla at FHD. The card also only averaged 26fps in Far Cry 6 at FHD, while the Radeon RX 6600 was running at 66fps. Despite this, because there was so much demand, the Radeon RX 6500 XT sold out in minutes when it launched, with prices then depressingly going even higher. After its panning in the press, though, AMD hasn’t launched an equivalently bad desktop GPU since.

4. AMD Radeon VII

Perfectly demonstrating that good-old-fashioned brute force can’t solve everything, AMD’s Radeon VII largely sunk without trace when it launched in 2019. AMD’s Vega56 and Vega64 GPUs had recently rolled up late with underwhelming performance, and the company had nothing to woo cash-rich gamers looking for a high-end GPU. Meanwhile, Nvidia had caught AMD napping, and had already uncaged its RTX 2080 and 2080 Ti, introducing us to ray tracing and DLSS, while also running much quicker than AMD’s Vega GPUs.

Radeon VII had no ray tracing hardware, or AI matrix cores for that matter

AMD’s answer was to take the new Vega20 GPU it had developed for workstations, package it up in a gaming card, and hope it could force Nvidia’s top-end Turing cards into submission. With its GPU die surrounded by 16GB of super-fast HBM2 chips, Radeon VII had twice as much VRAM as Vega64, and a massive 1.02TB/s of memory bandwidth. Unlike first-gen Vega chips, Radeon VII’s GPU was also built on TSMC’s 7nm tech, rather than GlobalFoundries’ 14nm process, resulting in a much smaller GPU die and faster clock speeds. Radeon VII could boost to 1,802MHz at peak, compared to Vega64’s 1,546MHz.

Confident it had a killer graphics card under its belt, AMD slapped a $699 price tag on Radeon VII, putting it on the same level as Nvidia’s GeForce RTX 2080. But by this time we’d moved beyond solely relying on clocked-up GPUs and high-speed memory to improve performance. Radeon VII had no ray tracing hardware, or AI matrix cores for that matter. It also drew loads more power than the RTX 2080, its cooler made a horrible noise, and its gaming performance lagged behind the RTX 2080, even without ray tracing enabled.

Now pretty much forgotten, Radeon VII showed that AMD couldn’t just shoehorn as much old tech as possible into a massive graphics card and hope to win. If AMD wanted to compete with Nvidia, it needed to go back to the drawing board rather than doing more of the same.

3. Nvidia GeForce GTX 480

Nvidia did a proper comedy step on a rake with Fermi in 2010. Its preceding GTX 280 cards had been getting a fair old battering from ATi’s formidable Radeon HD 5870, and Nvidia needed to stage a comeback. Its returning blow came in the form of the GTX 480, which turned out to be one of Nvidia’s biggest turkeys.

Bafflingly, Nvidia gave this hot, noisy, power-hungry monster a $499 price

It didn’t look bad on paper. There were 480 stream processors packed into a sizeable 529mm² GPU die, and the card came equipped with a massive 1,536MB of GDDR5 VRAM. Produced on the same 40nm TSMC node as the HD 5870, it should have been a winner.

But in practice, the GTX ate power supplies for breakfast, regularly drawing over 100W more than the Radeon HD 5870 at peak load. That would have been forgivable if it was loads faster, but it wasn’t. It inched ahead in a few games, but in some titles the older, cheaper and more power-efficient HD 5870 was still in front. Meanwhile, the hot-running GPU required loads of cooling power to keep it in check, resulting in the fan on Nvidia’s reference blower cooler spinning at an ear-assaulting speed.

Most bafflingly of all, Nvidia then gave this hot, noisy, power-hungry monster a price of $499 / £420, while the HD 5870 could be bought for just over £300. There was simply no point in buying the GTX 480 when the older competition was so much better balanced. We were entirely unsurprised when the rumoured dual-GPU version, reportedly called GTX 490, was never released.

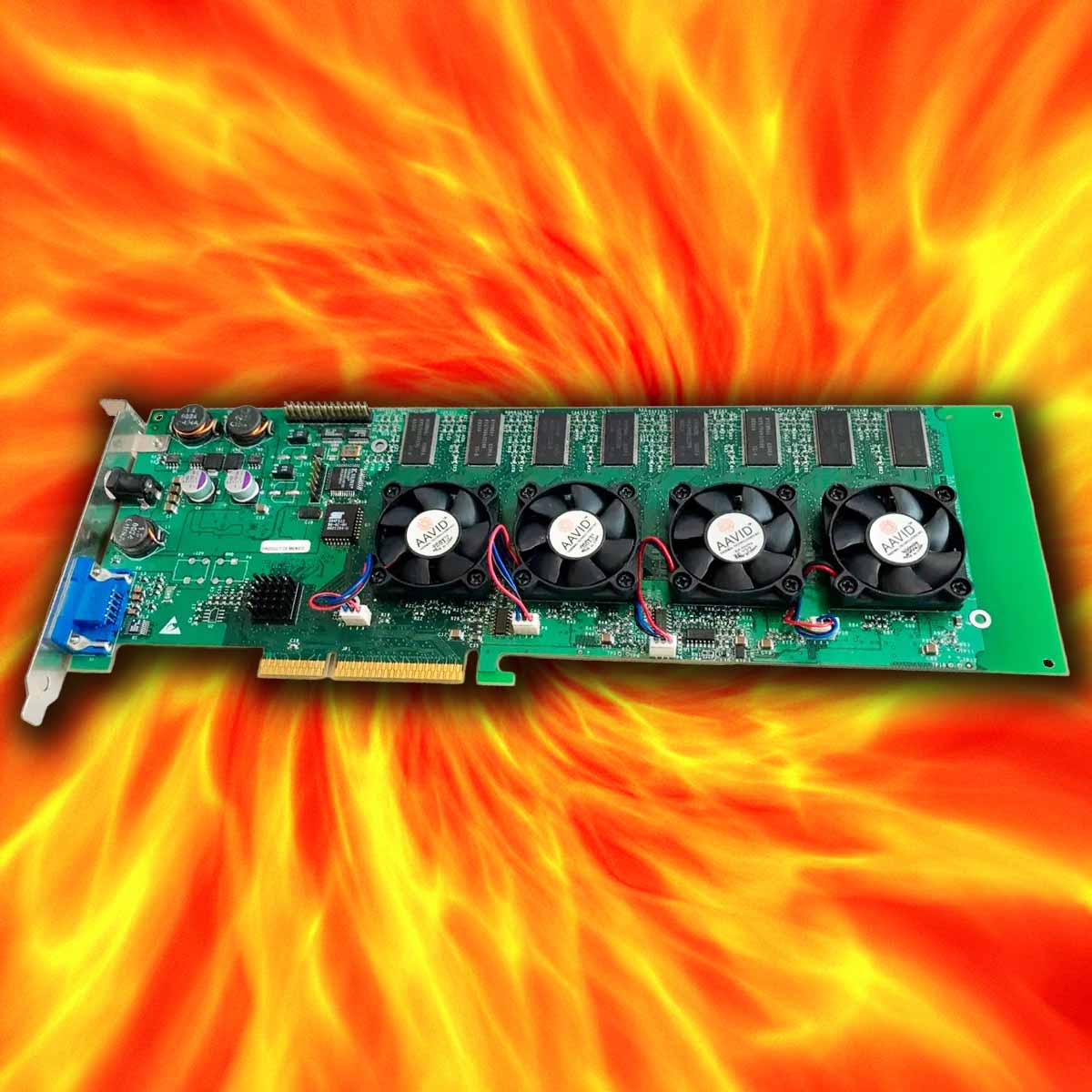

2. 3dfx Voodoo5 6000

If you’ve ever wondered how 3dfx plummeted from graphics king to financial ruin in such a short space of time, this multi-chip monster gives you an idea of Voodoo HQ’s warped thinking at the time. This one hurts, because we all loved 3dfx before this point, and still regard the original Voodoo chipset and its successor as two of the top 10 GPUs ever. We had high hopes for the new cards too, with their promise to finally bring 32-bit colour to Voodoo, as well as hardware anti-aliasing to smooth out nasty jagged edges.

But in 2000, the eagerly anticipated Voodoo5 lineup rolled up to the graphics party over a year late, with an insatiable thirst for power, bizarrely high prices, and bafflingly disappointing performance. There was also no hardware transform and lighting (T&L), meaning the new VSA-100 chip underpinning these cards technically wasn’t even a GPU. Meanwhile, in the time it had taken 3dfx to push Voodoo5 stumbling out the door, Nvidia had not only turned PC graphics on its head with its T&L-equipped GeForce 256, but even unleashed the next-gen GeForce 2.

This one hurts, because we all loved 3dfx before this point

To make matters worse, only two cards from the widely-advertised new 3dfx lineup made it out into the real world, the two-chip 64MB Voodoo5 5500 and 32MB Voodoo4 4500. There were two cards missing – the 32MB Voodoo5 5000 and flagship Voodoo5 6000, with teething and production problems delaying these cards even more.

With four VSA-100 chips linked together in SLI, and a massive 128MB of memory (32MB per chip), the 6000 had a colossal PCB, and even required a chunky extra power supply. We’re not talking about a couple of Molex connectors here either – it actually needed a proper external power brick with a kettle lead.

Only about 50 were ever made, and while we never got to officially test one at the time, some folks have managed to get hold of cards and bench them retrospectively. I also remember benchmarking the 3dfx Voodoo5 5500 against GeForce 2 cards at the time, and its performance was much closer to budget GeForce 2 MX cards than GeForce 2 GTS, despite having a similar price to the latter. The game was up when Nvidia released GeForce 2 Ultra, offering phenomenal performance from a single chip, and the 3dfx Voodoo5 6000 was still nowhere to be seen. Even if it did come out, it wouldn’t be much faster than a GeForce 2 GTS, while probably costing twice as much money.

It also didn’t help that 3dfx had made a rod for its back by bringing all graphics card manufacturing in-house, rather than just distributing chips to board partners. With massive delays, production woes, disappointing performance, and lacking the latest features, 3dfx was already onto a loser. Meanwhile, a ferocious back-and-forth legal battle between 3dfx and Nvidia over patents ate into the company’s resources. Soon the whole 3dfx house came tumbling down, with Nvidia acquiring the brand and hoovering up all the assets. There’s a reason why no one has made a quad-chip gaming card since.

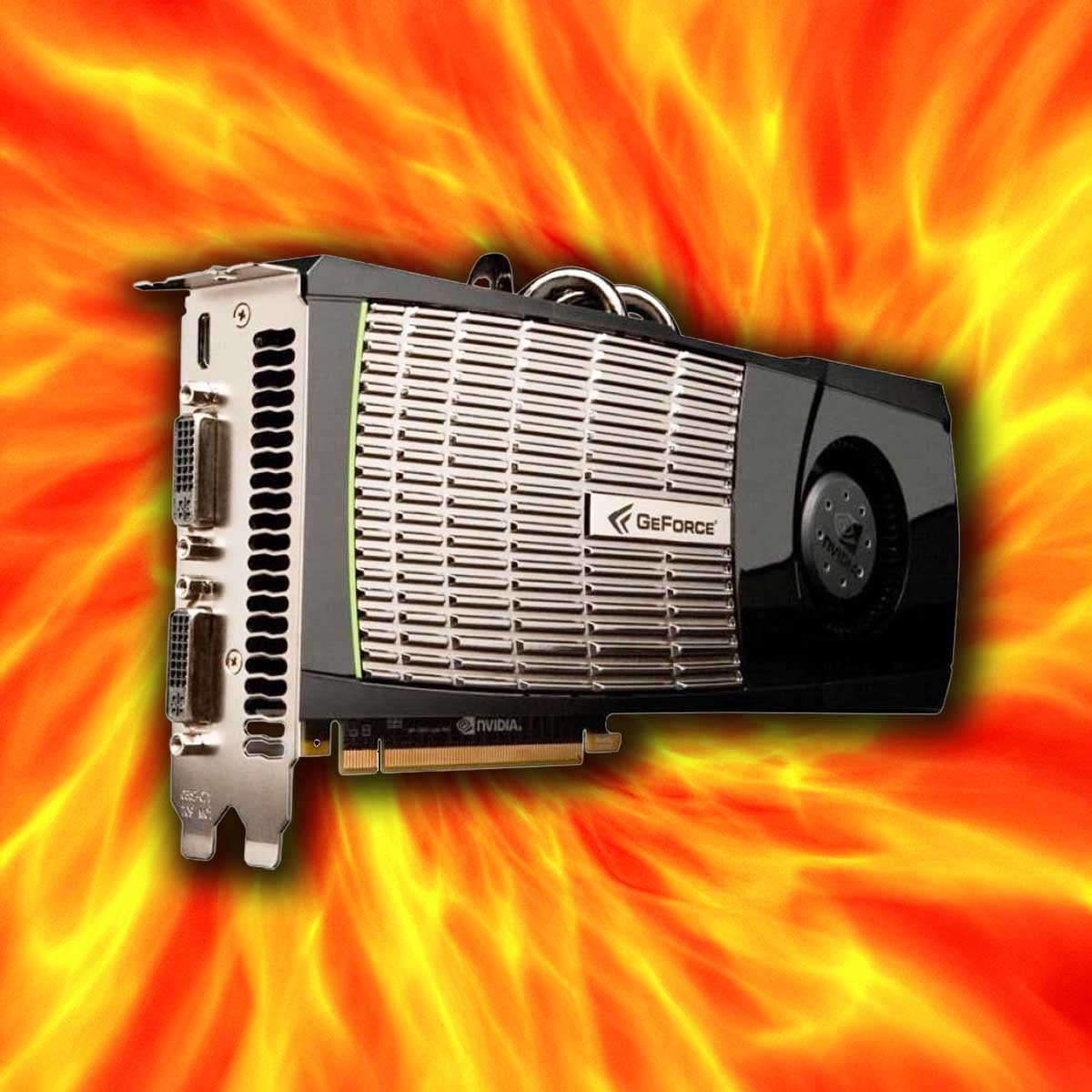

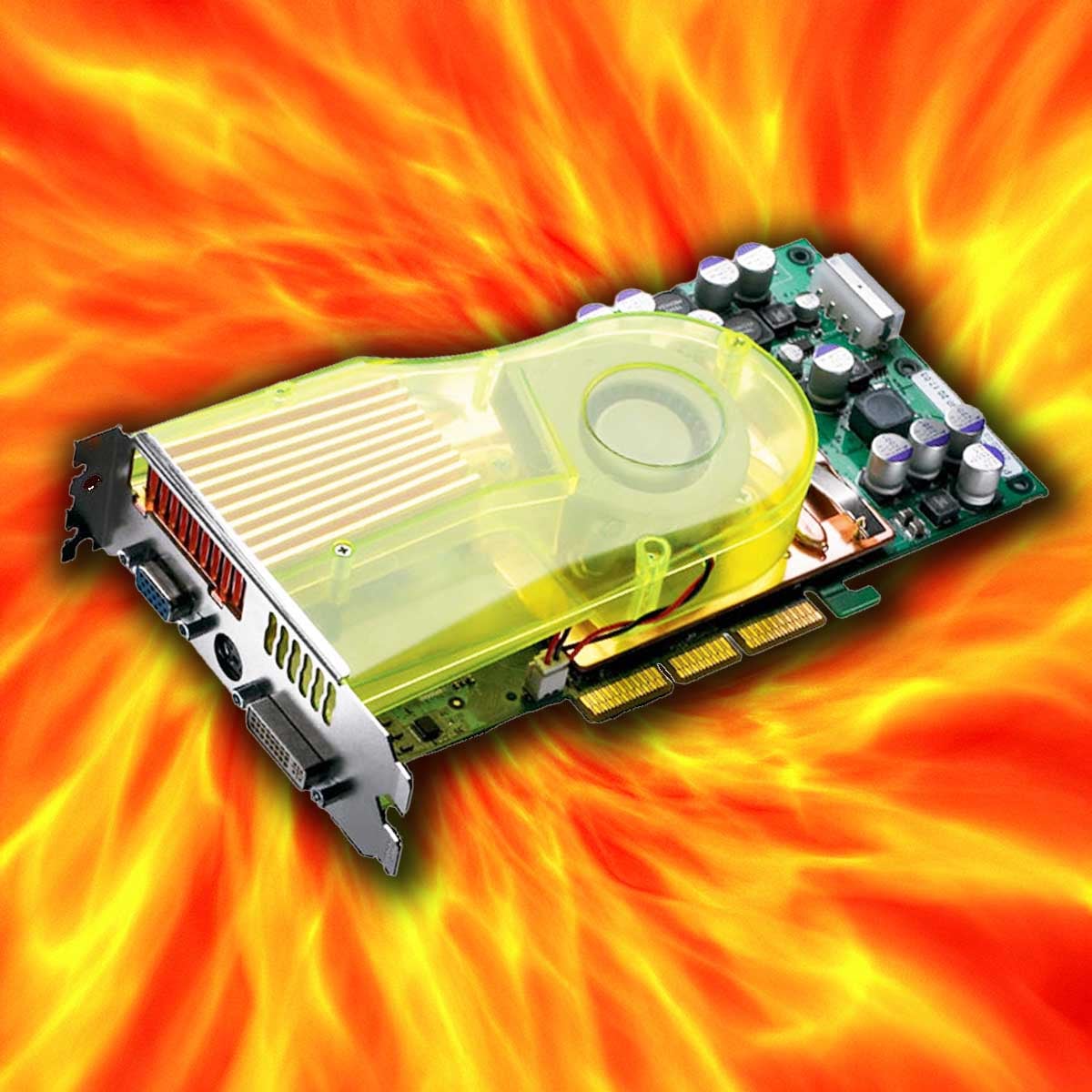

1. Nvidia GeForce FX 5800 Ultra

Sounding like a gasping Nazgul using a miniature high-powered hairdryer, this translucent red and green contraption offers a rare glimpse of Nvidia slipping up and landing on its face. In fact, Nvidia got this card so wrong it ended up releasing a comedy video to lampoon it.

Depicting a mythical meeting about ‘The Decibel Dilemma,’ Nvidia execs were shown agreeing to make the loudest cooler ever, in a bid to make the ‘Harley Davidson of graphics cards.’ FX 5800 Ultras ended up being strapped to leaf blowers and coffee grinders, while people waved them at their hair. It’s hard to imagine the serious corporates at Nvidia doing this now, but back then the company decided to hold up its hands and laugh at itself.

A someone who tested this card for review when it first came out, I can confirm that it absolutely made a horrible racket. Its main problem was a new cooler design that Nvidia christened FX Flow. The aim was to cool the hot-running GPU and memory in one go with a single fan. A single-piece copper plate and heatsink shifted heat from the GPU and VRAM on the front, with another heatsink on the back for the rest of the memory. A tiny blower fan then whirled at high speed to move all the hot air, with airflow forced through plastic ducting and pushed out the back.

It worked, in that it kept the GPU cool, but its noise was comically bad – I’ve never heard anything like its loud, high-pitched whir since. It ended up being nicknamed the ‘dustbuster’ for good reason. Sadly, though, there was a lot more wrong with GeForce FX than the cooler on the 5800 Ultra.

Its noise was comically bad – I’ve never heard anything like its loud, high-pitched whir since

Bringing us Nvidia’s first Shader 2 architecture in March 2003, ATi’s 9700 Pro, which came out in August 2002, was better at pretty much everything. While the 9700 Pro had eight pixel shaders, FX 5800 Ultra only had four, and while comparing these numbers isn’t exactly like-for-like, the Radeon 9700 Pro was significantly faster.

It also didn’t help that the FX 5800 Ultra’s new high-speed GDDR2 memory was only attached to a 128-bit wide interface. Meanwhile, the Radeon 9700 Pro’s older DDR VRAM had a wider 256-bit wide interface, resulting in much more bandwidth, despite the older memory tech. ATi then added further to Nvidia’s woes by introducing the higher-clocked 9800 Pro in the FX 5800 Ultra’s launch month.

ATi’s GPUs were faster, didn’t make an annoying noise, didn’t require more than one expansion slot, and they were often cheaper too. Nvidia pulled this all back with the superb GeForce 6000-series later, but this is a period we expect Jensen prefers to forget. Next time you complain about your noisy graphics card, remember it could be much worse.

Dishonourable mentions

There were plenty of candidates for this list, but we wanted to focus specifically on 3D gaming cards, and we also only wanted to list GPUs that were bad, rather than just disappointing. If you step outside that zone, there are plenty of other graphical atrocities, though. The original CGA graphics standard is an obvious one. Back in the 80s, the PC’s colour graphics adaptor could only display four colours at once, with a chunky 320 x 200 resolution. What’s more, the default palette for some reason was cyan, magenta, black and white – it made games look horrible.

Other graphical disasters along the way include Intel’s Larrabee project, which attempted to turn several old Pentium cores into a GPU, and ended up never making it off the ground. Back in the 1990s, S3 Virge was also rubbish compared to 3dfx Voodoo and PowerVR accelerators, but we’ll let it off because it technically got there first.

We could also mention the fact that many of Nvidia’s latest GPUs have had weirdly small VRAM allocations, from the 8GB RTX 4060 Ti to the 12GB RTX 4070 Ti, and that AMD’s GPUs have been comparatively poor at ray tracing until this year. However, a GPU needs to be spectacularly misjudged to make it to our list, rather than just having a disappointing amount of memory.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this trip down memory lane and had a laugh with us. At the other end of the scale, you can also read our guide to the top 10 CPUs ever, where we chart the chips that made all the difference to our PCs.