Having launched high-performance 12th Gen Core H-series chips for gaming laptops at the turn of the year, attention now turns to P- and U-series processors from the same Alder Lake family.

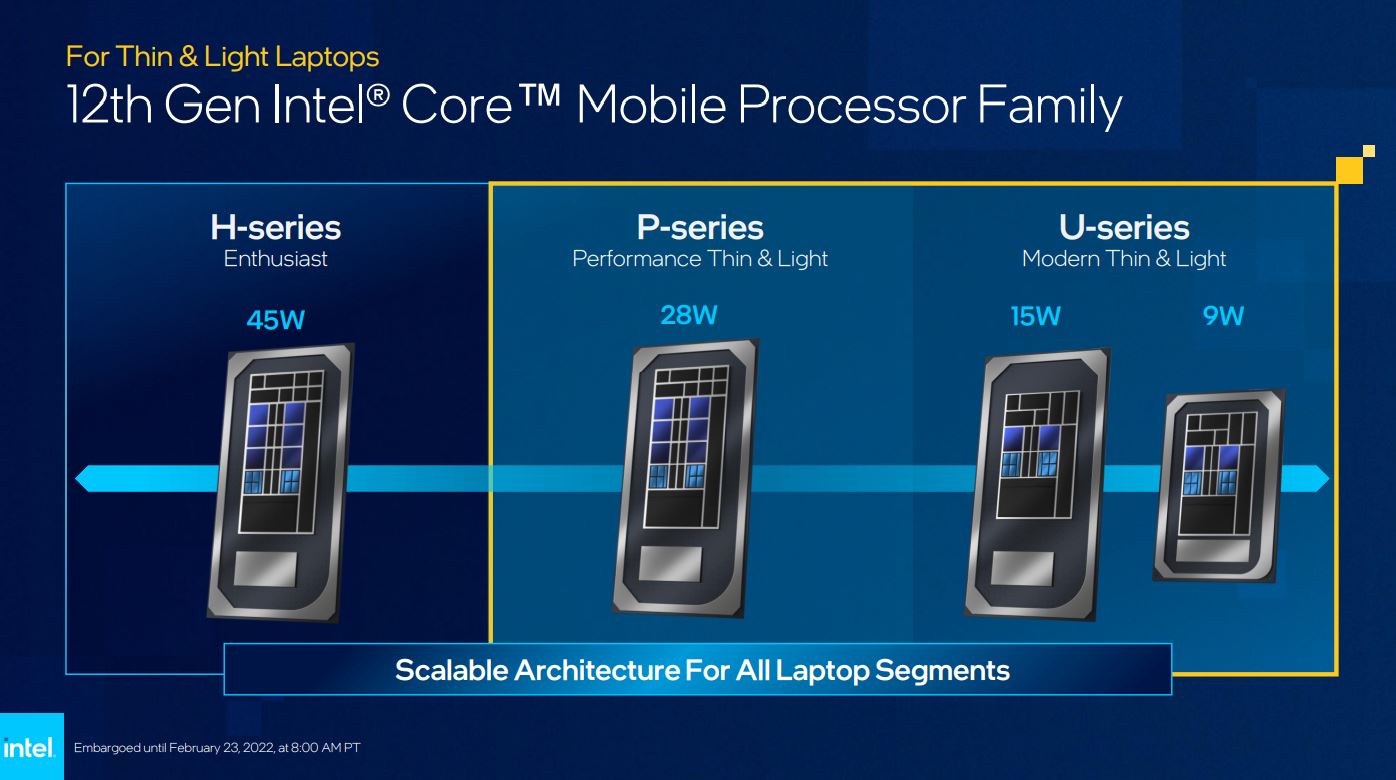

As a refresher, Intel segments the latest mobile processors depending upon nominal power budgets and use case. H-series is aimed at the gaming enthusiast and plumbed with a 45W TDP, though power does spiral much higher if the laptop maker chooses to do so. It is not uncommon to see the best of H-series pull over 100W for short durations.

Next up is the P-series. Primed for performance thin-and-light laptops, a base 28W TDP enables them to be automatic choices for 13-15in laptops under 2kg, presumably with a discrete graphics card in tow.

U-series, meanwhile, is the destination for modern thin-and-light laptops generally eschewing discrete graphics. Offered in 15W and 9W TDPs – though, as usual, configurable by the OEM to suit a particular chassis or market – these chips ought to offer the best battery life.

Announcements for P- and U-series follow on quickly after rival AMD’s unveiling of Ryzen 6000 Series mobile. This means the duo has specific solutions aimed at 45/28/15W TDPs, and both want to be in as many laptops as possible in 2022, hopefully at the direct expense of each other.

It is worth getting acquainted with the underlying Alder Lake architecture and use of hybrid-core technology for purposes of this editorial; the resulting 12th Gen Core mobile chips use it in interesting configurations.

P-series examined

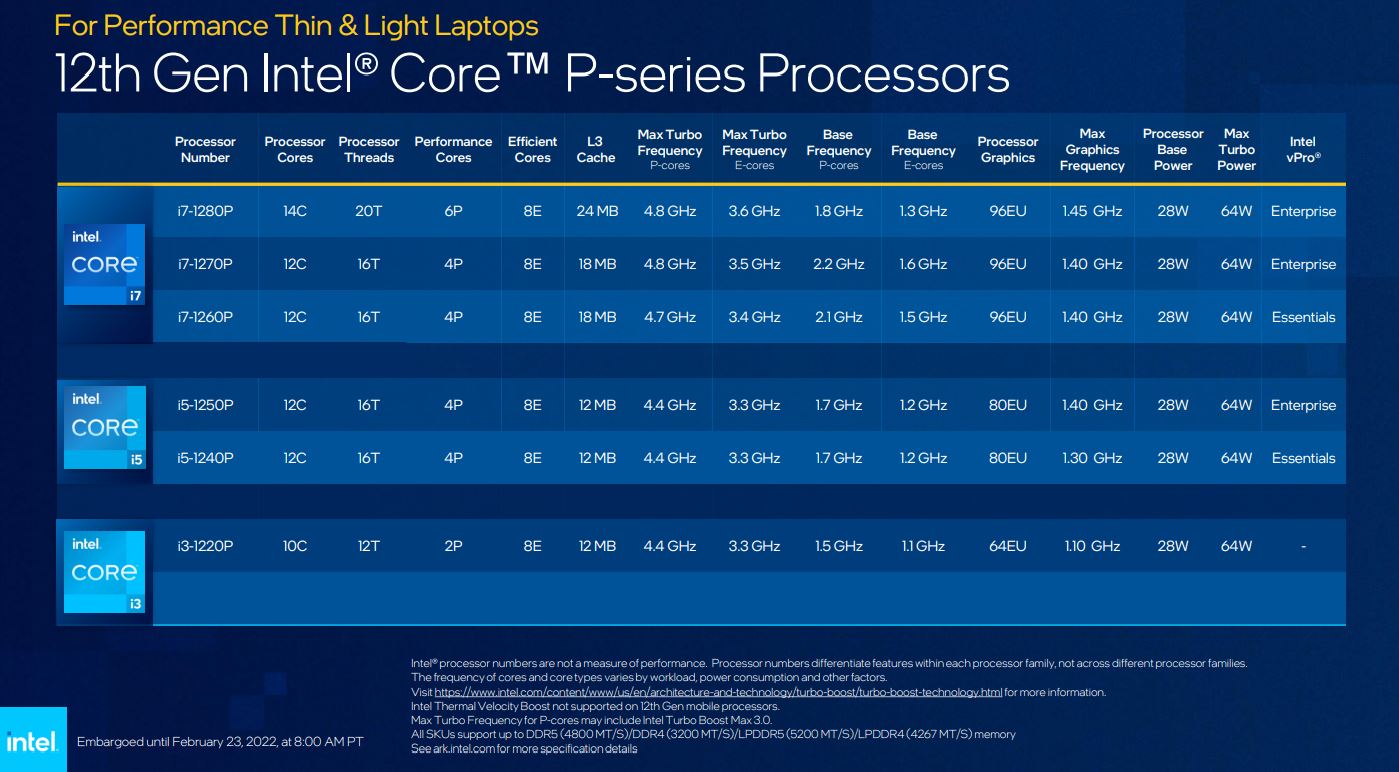

Understand that P-series doesn’t mean only Performance (Golden Cove) cores are used from Intel’s hybrid approach. Every one of the six chips in this line-up is imbued with a combination of Performance and Efficient cores, along with varying horsepower for integrated graphics.

As you can see from the Intel-supplied slide, there is no Core i9 present. It’s somewhat strange to see differing core-and-thread levels within one family, but there you go. Core i7-1280P replicates the 14-core, 20-thread topology of H-series processors, right down to the mix of six hyperthreaded Performance together with eight non-HT Efficient. Really, this top-bin P-series offering is a power-restrained version of an H-series processor.

Moving on down, 12 cores and 16 threads is consistent across the next two Core i7s and both Core i5s. There ought to be a reasonable benchmark gap between Core families, however, because i5 has less L3 cache, is clocked in lower, and features fewer graphics cores.

Last but not least, Core i3 shifts down to 10 cores and 12 threads. Having only two Performance cores feels stingy, so Intel instead relies on the Efficient ensemble to get the job done. It’s therefore hard to predict how, for example, Core i3-1220P compares against Core i5-1240P – changing the number of cores and their composition is confusing.

The 28W power budget is a base guide only. Able to spool all the way up to 64W and still remain within Intel specification, there is opportunity for a P-series chip to consume more long-term power than an H-series one. To be truthful, Intel’s power budgets are all over the place. This may lead to consumer bemusement when one laptop, remaining at 28W, is inferior to another, touting the same chip ramping power to 40W or so.

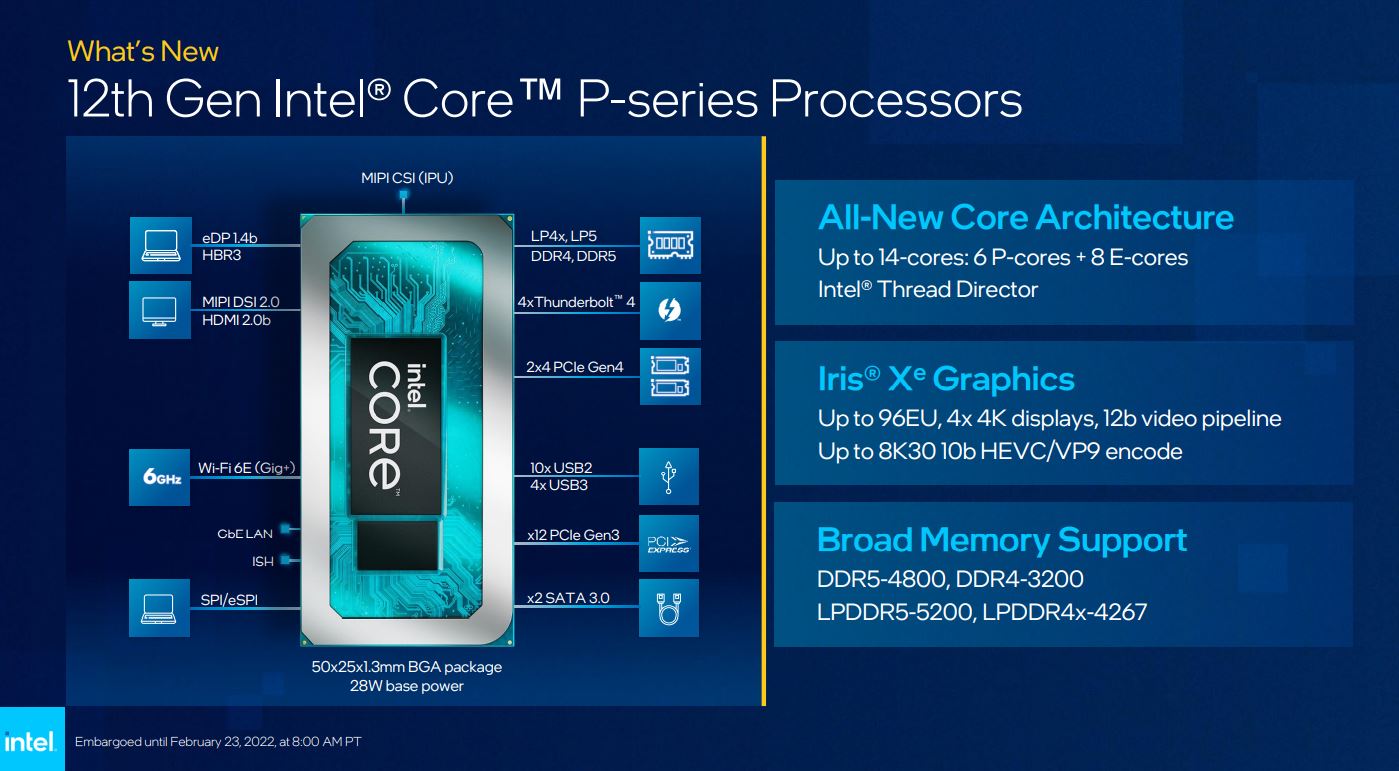

A simplified block diagram is instructive insofar Intel mandates either DDR4 or DDR5 memory, depending upon how the OEM sees fit. In lower-end SKUs designed for cost-sensitive markets, we reckon cheap DDR4 is the only way to go, whilst notebooks wanting best-in-class performance will engage the full bandwidth might of DDR5-4800.

Two PCIe 4.0 x4 lanes are handy to hang super-fast storage off, and a further 12 PCIe 3.0 lanes are sufficient for the usual array of peripherals. No direct mention is made for the link between the chip and direct-attached graphics, but we know there’s a PCIe 4.0 x8 interface present. Intel’s desire to push SoC-integrated Thunderbolt 4, presented as USB-C, comes at the expense of fewer USB 3.0 ports.

U-series examined

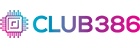

Dropping down to a nominal 15W TDP brings five Core processors and a single Pentium and Celeron into play. Chips top out at 12 threads, composed mostly of Efficient cores, and thus look weaker on paper than rival AMD 15W solutions housing up to 16 threads of full-fat Zen 3+ power.

It’s somewhat amusing to see Maximum Turbo Power set to 55W, which is almost 4x the base, and we’re intrigued to see which laptop makers are brave enough to install this rating on super-slim solutions. Going by our experiences, most will opt for a 15-25W band.

The oddest pair are non-Core processors. Having a single Performance core and four Efficient leads to a 5C/6T topology for Pentium, which is something we’ve not seen before. The sole Celeron representative is reckoned to have a 5C/5T design, though that seems impossible if a single Performance core is present. This is a typo on Intel’s part.

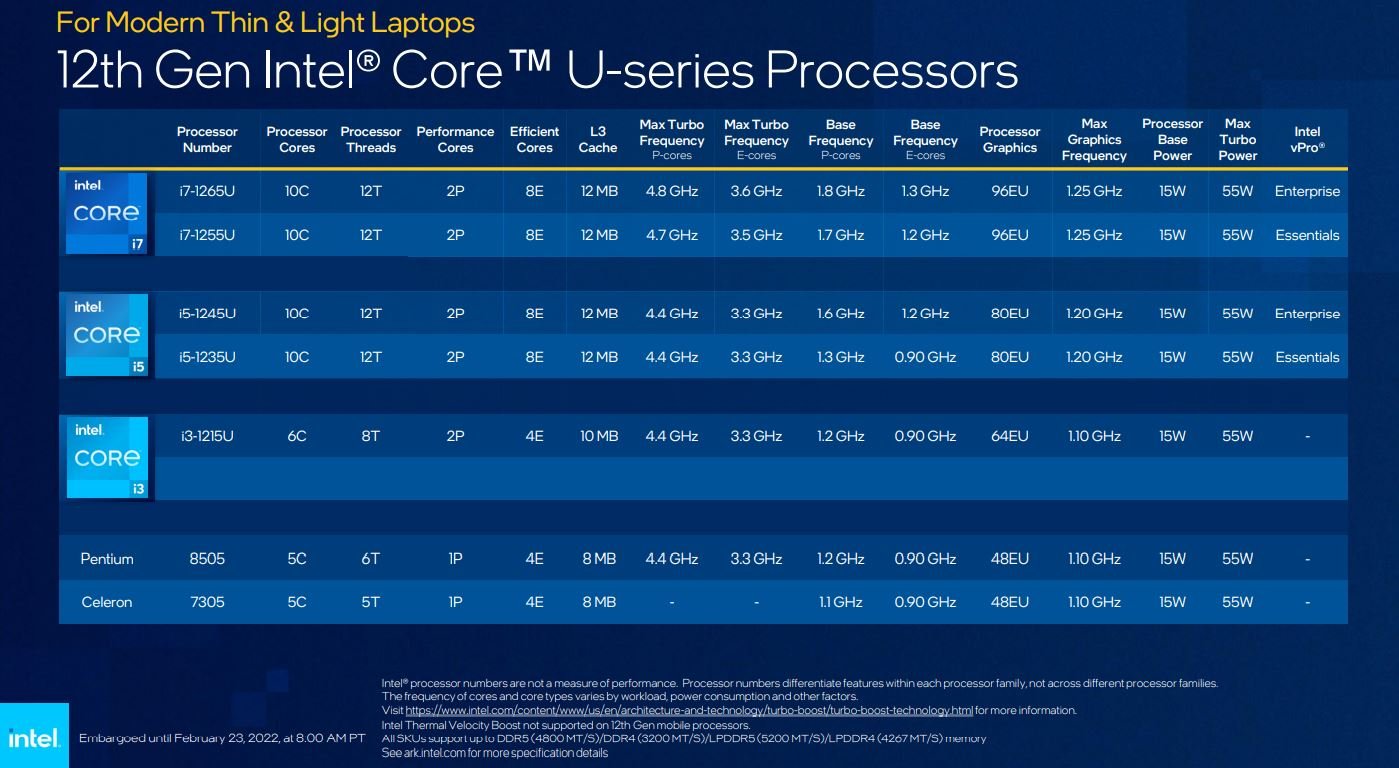

Going all the way to 9W doesn’t give the Alder Lake architecture much energy budget to bargain with. Rising to a potential 25W, we’d hazard these models have a very low all-core speed, reflective of meagre power ratings. It’s implausible a 10C/12T Core i7-1260U can run demanding multi-core applications anywhere near as quickly as a Core i5-1240P. The logical assumption is U-series processors will leverage the short-term power more aggressively than P-series.

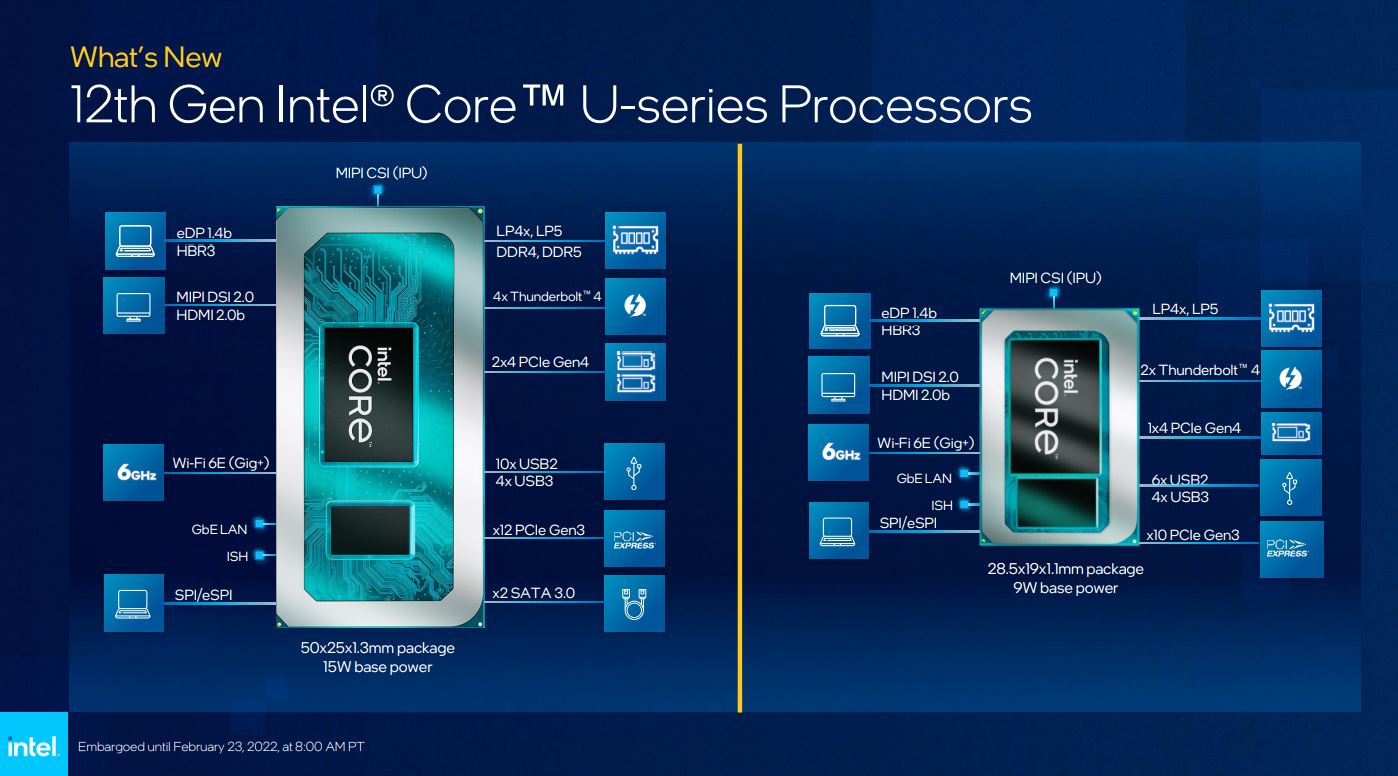

15W U-series employs an identical BGA package, leading us to believe these processors are, in fact, toned-down versions of P-series. The feature-set and connectivity are identical, too, lending further weight to this assertion.

9W U-series, meanwhile, is destined for the absolute thinnest, smallest laptops and is duly presented in a much smaller BGA form factor. It keeps all the important goodies from the bigger SoCs, and losing a few lanes here and a second M.2 slot there is eminently sensible. Considering the intended environment, discussions regarding discrete GPUs are unwarranted.

Performance

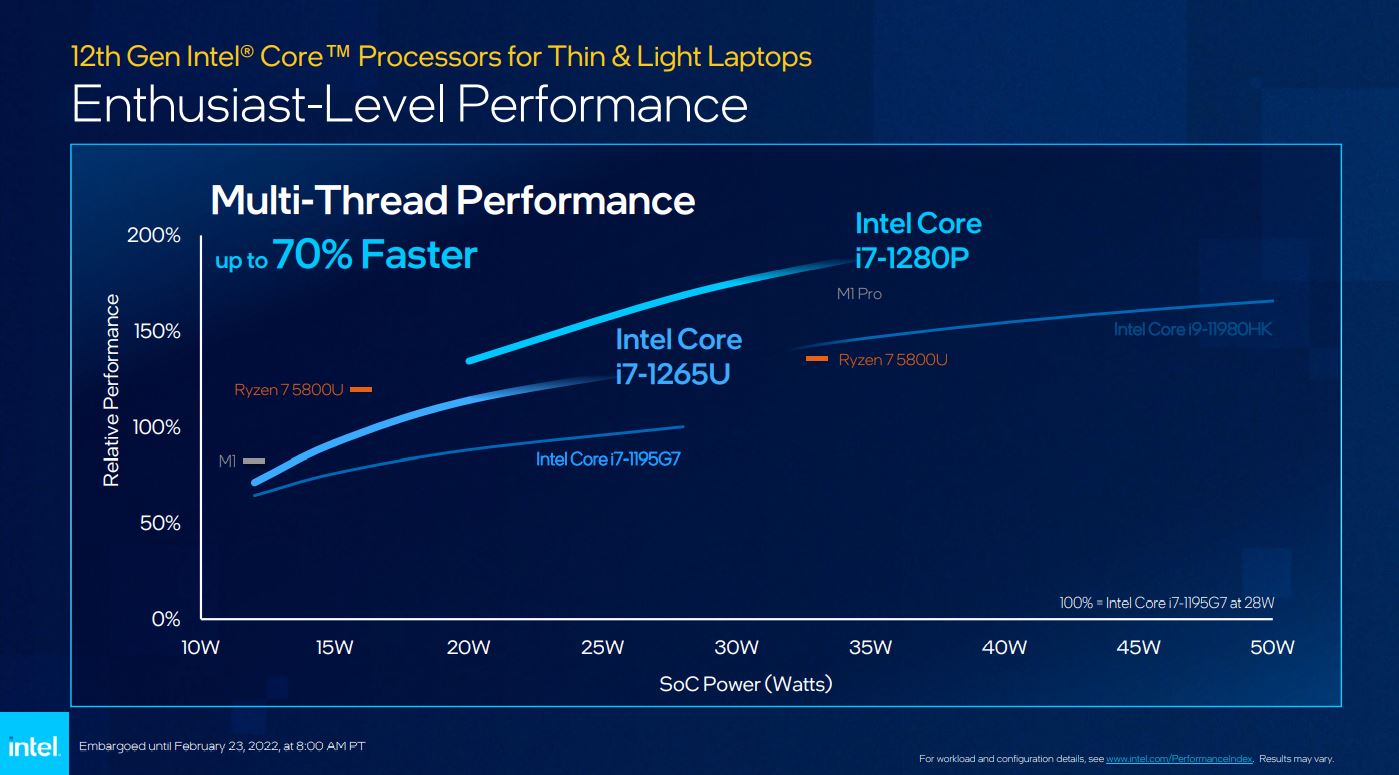

Intel has high hopes for both new Alder Lake mobile families. In a slide unashamedly promoting the new series, Intel actually reckons the CPU portion of the U-series, as represented by Core i7-1265U, is not as efficient as last-gen Ryzen 7 5800U. Just as well Intel isn’t comparing to Ryzen 7 6800U.

Moving up the wattage spectrum leads to P-series dominating the landscape. Offering class-leading relative performance across a 20-35W range, we’re sure AMD will have something to say about that – Zen 3+, after all, is designed with efficiency in mind.

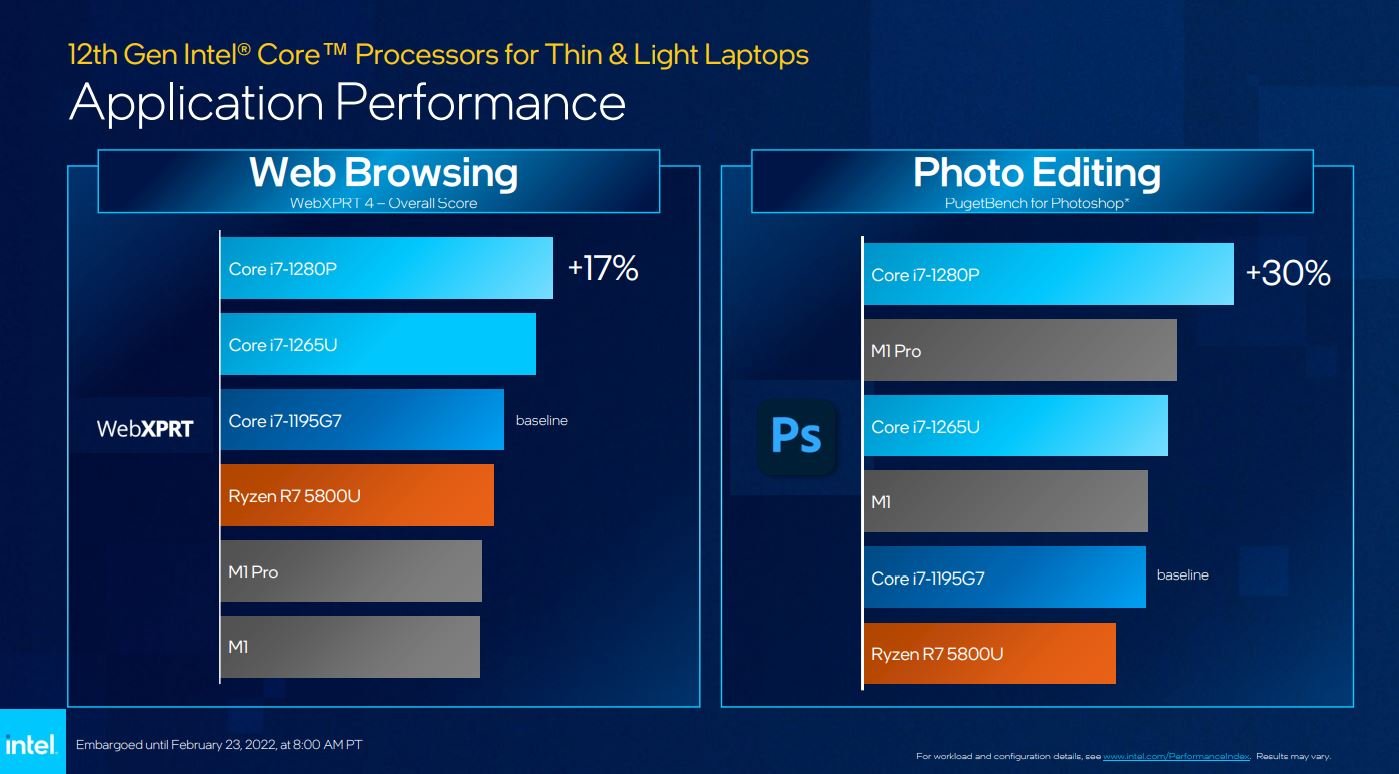

Intel then trots out further slides reinforcing the generational improvement and supposed AMD-beating performance in applications most partial to Alder Lake love.

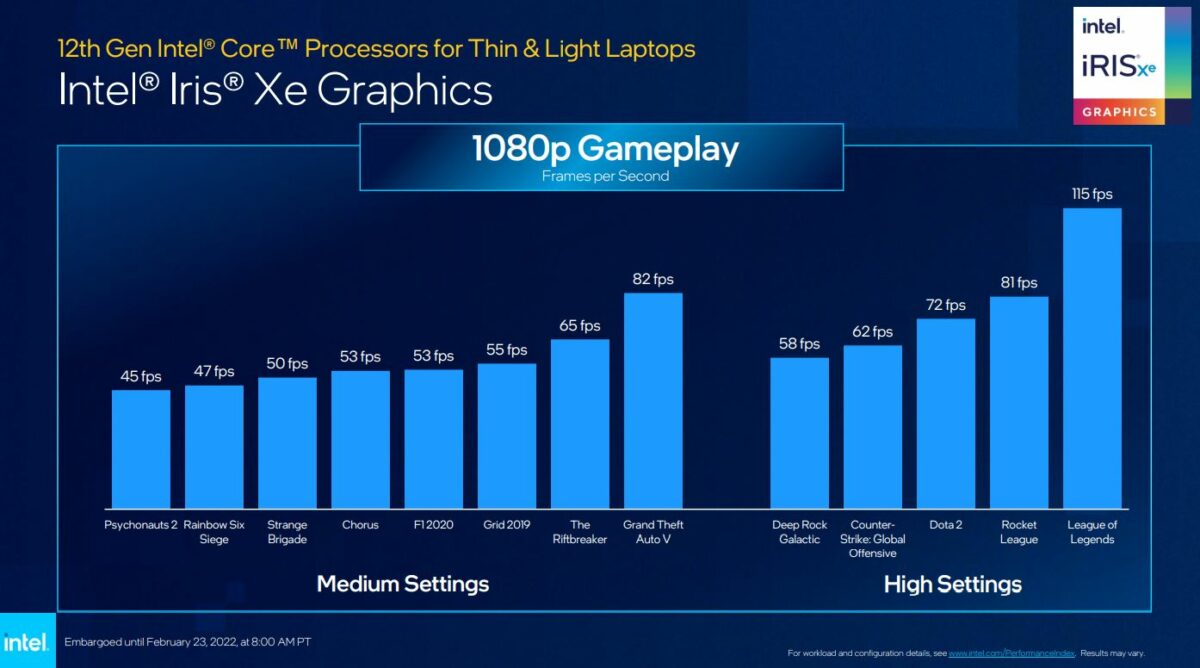

Topping it off with the distinct knowledge that Intel Iris Xe Graphics, based on older technology, are likely to be no match for RDNA 2 in Ryzen 6000 Series mobile, Intel sensibly dismisses competition and posts scores in isolation. Exactly what you do when the rival is way too strong in a particular department.

The Wrap

Much in the same vein as desktop processors, Intel releases the full cornucopia of mobile artillery in two stages. H-series served as the vanguard; now P- and U-series combine to fill out Team Blue’s mobile ambitions for 2022.

The hybrid Alder Lake architecture is very much on show across both ranges, and if you believe manufacturer-produced benchmarks, 12th Gen Core ought to do well.

Exactly where these new chips fit into the wider mobile landscape – 12th Gen mobile vs. Ryzen 6000 Series mobile is a mouth-watering clash – can only be determined by independent reviews. As it stands, the obvious winner is the consumer buying a cutting-edge laptop in 2022; there appears to be no bad choice.